When puberty blockers were banned in June 2024, the legislation included a clause stating that those currently on blockers would not be medically detransitioned, and could continue care if adopted by an NHS GP.

Only one NHS GP practice, WellBN in Brighton, agreed to take over this care, with trans adolescents and families from across Great Britain moving to their care. Patients have reported extremely high rates of satisfaction with this care.

In May 2025 ICB Sussex (ICB = Integrated Care Board, the level of bureaucracy above a GP practice and below NHS England) and NHS England launched an investigation into this care. The investigation has already caused a high level of harm to trans adolescents and families. Essential care is under threat of being taken away, with a threat of forced medical detransition. One person (I can’t share their identity) put this situation into a series of illustrations, capturing powerfully the current situation. This has been shared on instagram, but for those who don’t use it, they gave me permission to share here. I’ve added a bit of extra context.

Image one captures the ICB’s allegation of trans adolescents having been exposed to ‘potential harm’. What we instead have seen, is young people thriving and excelling through access to respectful affirmative healthcare.

[Description of image 1 “Potential Harm”: One trans young person is winning at sports; One is dreaming of a happy future relationship and marriage; one is hanging out with friends; one is doing their school work; one is playing the piano while proud parents watch; one is going shopping with a parent – while professionals write up reports of potential harm]

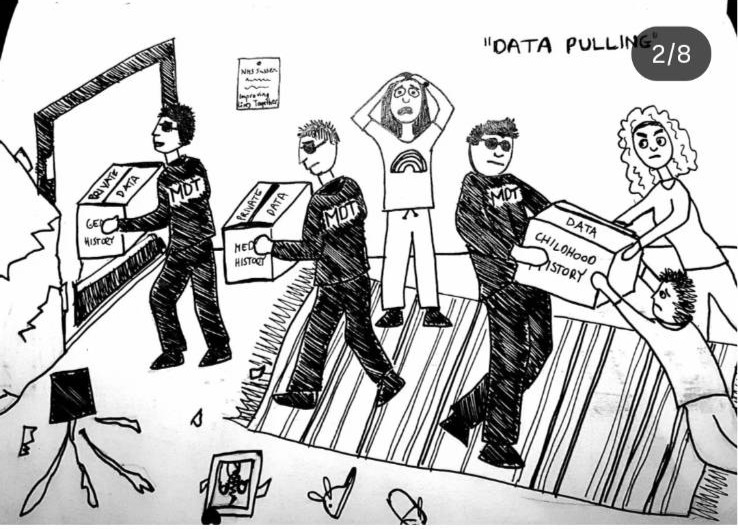

Image two captures the NHS’s approach to data collection. GP practice patients refused consent for the ICB taking their private patient data. GP practice patients, adolescents and parents, added notes to their files formally refusing permission to share their data. The GP practice did not want to share this data, and refused for several months. The GP offered anonymised data – the ICB was not interested in anonymised data. The ICB and NHS England stated that consent was not necessary due to ‘patient safety concerns’ despite no evidence of harm. The ICB finally threatened to cancel WellBN’s whole NHS contract, closing down a GP surgery with 25,000 patients, if they didn’t hand over patient data. WellBN at this point folded and handed over all trans children’s data. Information commissioner office complaints have been submitted.

[Description of image 2 “Data Pulling”: A house is being trashed with objects broken. Men in black suits (with the words Multi-disciplinary team on their top) are forcibly removing boxes of data, while adolescents and families try to keep hold of them. The boxes are labelled ‘private data’, ‘gender history’, ‘medical history’, ‘childhood history’.]

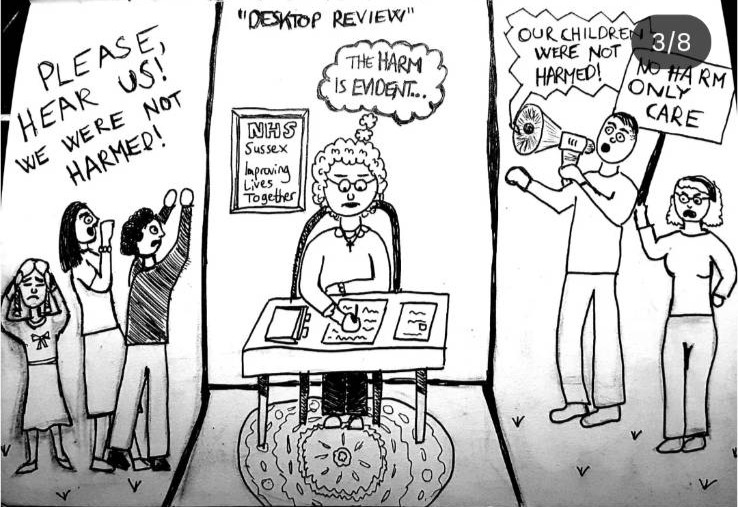

The third image covers the evaluation of patient harm. A patient harm investigation is being conducted without speaking to a single trans adolescent or family. It is being conducted purely based on clinical notes. The conclusion has been pre-determined with the investigation clearly considering affirmative care inherently a form of harm. Trans adolescents and families have prepared testimony on the reality that not only has there been no harm, their care has been excellent. Trans adolescent and family voices are not being heard.

[Description of image 3 “Desktop Review”: Adolescents and families are shut outside, using loud speakers to say ‘Please hear us, we were not harmed’; ‘children not harmed’, ‘no harm only care’. Inside, behind thick walls sits the head of the investigation team doing a ‘desktop review’ writing ‘harm is evident’.]

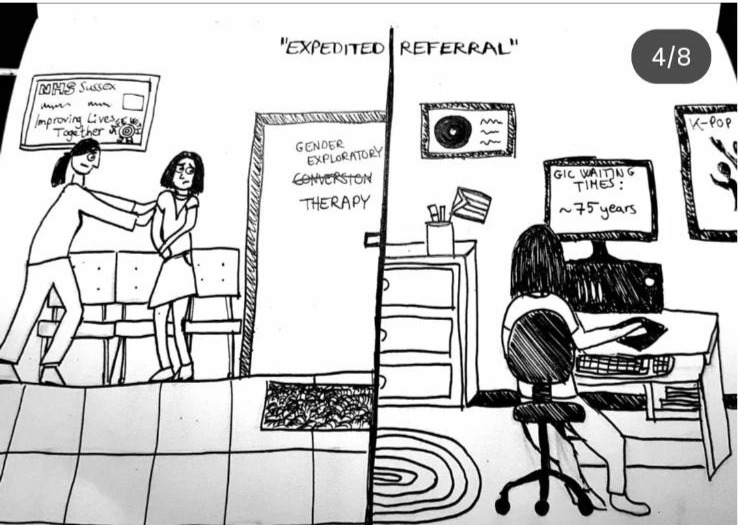

The fourth image focuses on the ICB’s plan to close all WellBN Care and refer patients elsewhere. Trans youth who are under 17 are to be forced to into gender clinics that offer conversive talk therapies focusing on investigating trans identities. 17 year olds will join waiting lists for adult care that stretch into years and years long.

[Description of image 4 “Expedited Referral”: A scared young person is being pushed into a room. The room was labelled ‘conversion therapy’. The word conversion has been crossed out, and in its place the words ‘gender exploratory’ therapy are now scrawled. In another scene a slightly older adolescent sits at a computer where the screen states ‘Gender Identity Clinic waiting times: 75 years].

Image 5 covers the preferred NHS approach for trans youth, gender clinics that focus on invasive, traumatic and inappropriate questioning of trans youth.

[Description of image 5 “Holistic Assessment”: Worried looking parents embrace a worried looking adolescent on one side. Ahead of them is a barrier labelled ‘caution no treatment ahead’. Behind the barriers are six faces with word bubbles ‘how do you feel about your penis?’; ‘do you get erections?’; ‘how often do you masturbate?’; ‘Are you sure you’re trans’?’; ‘Do you like girls’ underwear?’; ‘are you gay?’].

Image 6 focuses on the ICB’s intention for ‘assisted withdrawal’ of affirmative healthcare. This is forced medical detransition. It is abusive and harmful.

[Description of image 6 “Assisted Withdrawal”: A trans girl is having her long hair cut and facial hair painted onto her face; a trans boy is having breasts added; a young girl musician is crying while a professional says ‘don’t worry you’ll be singing with the boys in no time’]

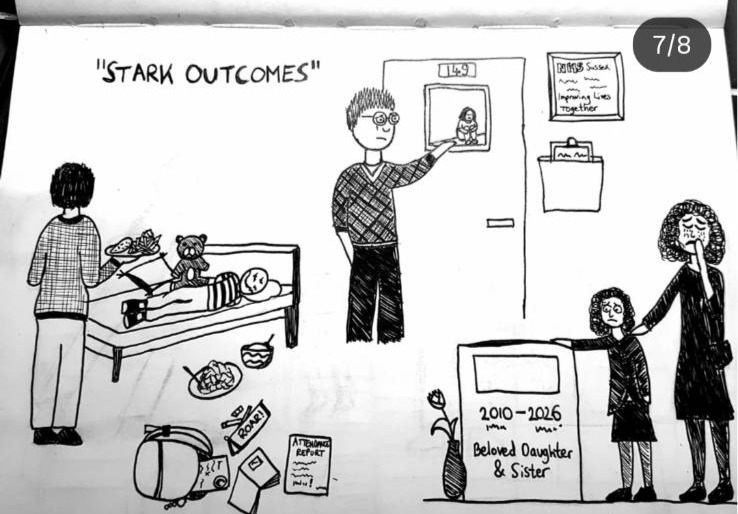

The ICB have stated that they expect the outcomes to be ‘stark’ for impacted trans youth ‘especially the younger ones’. This image powerfully captures the type of stark outcomes that the ICB is well aware of as possibilities, having included these risks in their own risk assessment.

[Description of image 7 “Stark Consequences”: The image shows various depictions of children and adolescents having serious mental health consequences, including school drop out, stopping eating, mental health crisis and death]

The eighth image captures the ICB and NHS England’s intended ‘robust tracking approach’. Now that they have full patient data on adolescent and supportive families, they intend to ‘robustly’ track these children and families, keeping their data for 20 years, and tracking what adolescents and families do next. They have stated that if they think families and adolescent will continue to access medication through private means, they will be reported by the ICB to social services. Families and adolescents feel extremely threatened, extremely unsafe. Many are trying to find ways to flee the country.

[Description of image 8 “Robust Tracking Approach”: A scary large figure with a magnifying glass stares down at a scared looking child, while parents try to pull the child away to somewhere safer]

The final image shows scared young people being pushed into a black hole.

[Description of image 9 “Improving Lives Together”: Scared young people, some of whom are crying are being pushed into a black hole. The adults pushing them in are saying statements like “just one of those stark outcomes”; “have to follow the guidelines”; “It’s not commissioned”; “the guidelines have shifted”; “there are trans kids?”; “the terms of reference sets this out quite clearly”.

Across all of the above images the artist has included ICB Sussex’s tagline ‘Improving Lives Together’.