[This is really long and is a live-note taking as I read through from pages 27-100 of the report. I won’t do beyond page 100]

Looking for balance

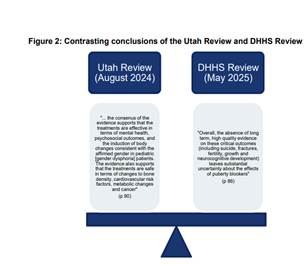

The following image is provided to illustrate contrasting conclusions of different reviews of the same evidence base.

One the left, and in favour of trans healthcare we have the Utah Review:

“”… the consenus of the evidence supports that the treatments are effective in terms of mental health, psychosocial outcomes, and the induction of body changes consistent with the affirmed gender in pediatric [gender dysphoria] patients. The evidence also supports that the treatments are safe in terms of changes to bone density, cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic changes and cancer” (p 90)

On the right, and opposed to trans healthcare we have the DHHS Review:

“Overall, the absence of long term, high quality evidence on these critical outcomes (including suicide, fractures, fertility, growth and neurocognitive development) leaves substantial uncertainty about the effects of puberty blockers” (p 86)”

The graphic suggests that the Vine review is going to have the difficult task of weighing up the benefits vs risks in this field where different reviews come to different conclusions on the same evidence base.

What is unstated, in presenting these two reviews in balance, is the type of evidence they are interested in.

They are asking very different questions.

On the left we see some evidence of benefit, for a treatment that is wanted by trans young people, with no evidence of harm. In a rights-based approach, this is convincing.

On the right, we see emphasis of a claimed a lack of rigorous long-term evidence on areas that are assumed to be a risk (suicide, fractures, fertility, growth and neurocognitive development) – without providing evidence that there are a notable or unmanageable risk. We are presented with the claim “uncertainty about the effects of puberty blockers” when the effects of puberty blockers are very well known, with no controversy in cis users.

These two are not of equal status, and presenting them as ‘in balance’ already gives the impression of a review looking for a performance of balance, rather than driven by the actual evidence.

Ignoring the impact of prejudice

There is a box on page 35 that is indicative.

Here the different views are presented:

“The Panel heard in consultation: · diametrically opposed interpretations of, and commentary on, the evidence base underlying the use of PB and GAHT, including criticism from several viewpoints of the methodology and conduct underlying all research; · from some clinicians who highlighted the role of expert opinion in EBM, and others who criticised a situation where opinion replaces evidence, particularly in clinical practices with, or where concerns may be raised of, a closed culture; · concerns of bias in research resulting from low sample size and uncertainty resulting from the lack of longitudinal studies, along with comments regarding the feasibility of studies such as Randomised Placebo Controlled Trials (RCT); and · from some clinicians who highlighted the accepted standards for EBM in current paediatric and psychological medical practice, and others who critiqued the use of these standards.”

All of this is presented without ANY consideration of a very clear reality that this is an area of healthcare significantly impacted by prejudice – where significant actors are fundamentally opposed to trans existence – where actors are proactively trying to shut down all healthcare for trans youth.

Recognition of ‘differing professional opinions’ in this field cannot be separated from the recognition of proactive movements, within healthcare professions, to outrule trans healthcare.

In 2026, in the face of politically and ideologically motivated campaigns against healthcare, from trans healthcare to abortion to vaccination, it is completely unacceptable for an evidence review to pretend that this is not a significant component of what is happening. It is impossible for any healthcare review to try to stay neutral to, much less in denial of the existence of ideological movements trying to eradicate healthcare.

Summary of the evidence

The Vine Review’s summary of the evidence is presented on page 36:

In summary, our conclusions are:

(a) we agree with the near consensus among international reviews (noting the conclusion of the Utah Review),42 that the evidence base underlying use of PB for young persons with gender dysphoria is limited;

(b) the reasons for that limitation include broadly that most studies have methodological limitations, are shorter term, observational only, risk selection bias and risk confounding in that outcomes often cannot be solely attributed to one intervention;

(c) the results of the JBI literature review are set out in further detail below, but in summary, JBI reported a low to moderate certainty trend towards short term psychosocial benefit in care pathways involving PB treatment, however, that effects varied by birth-registered sex, evidence quality is low and some studies reported no change or persisting body dissatisfaction;43

(d) there is no evidence that PB should always be used before starting GAHT;

(e) despite methodological limitations, there exists low quality preliminary evidence suggesting that PB, when used appropriately, can temporarily alleviate existing gender dysphoric distress which could otherwise exacerbate; and

(f) there is some evidence that PB impact bone health in the short to medium term. There is a paucity of evidence as to whether bone health is negatively impacted in the longer term, but bone health should be monitored.

A few thoughts on the above table:

Evidence quality: Amongst all the discussion of evidence quantity and quality (points a and b), there is no recognition of three really important points – 1) that the evidence base is similar to or better than the evidence base for many other areas of medical care 2) that, despite being used and studied for decades, there is no evidence of significant harm 3) that in the absence of any evidence of significant harm, discussions on evidence quality are driven not by medical concern, but by controversy driven by the concerns of those ideologically opposed to all trans healthcare. When we centre evidence base quality without recognising these points, we will set off chasing a phantom – seeking an evidence base that will never be good enough for those who are ideologically opposed to trans healthcare.

Double standards: (On page 37 this double standard is even more clearly stated – the evidence base for use of puberty blockers for precocious puberty is stated thus “when used for central precocious puberty, PB are “generally well tolerated, with no clear evidence of harm to bone health or reproductive function, and uncertain effects on cognition and psychosocial outcomes but further research is required”. Uncertain impacts on cognition and psychosocial outcomes is not a justification for banning healthcare for cis individuals – only for trans healthcare.

Benefits: Here again we see puberty blockers held to an inappropriate evidence base of ‘benefits’. Short term psychosocial benefit is presented as somewhat inconsequential, despite being a key purpose of a puberty blocker. Puberty blockers would never show ‘long-term psychosocial benefit’ because they are not supposed to be used longer-term, and longer-term differences between those accessing or not accessing healthcare would a) be unethical to study in a randomised trial and b) would be confounded by those who also access HRT. The finding of ‘some studies reported no change or persisting body dissatisfaction’ is presented as though a negative, when this is entirely EXPECTED for puberty blockers. Puberty blockers are never expected to resolve existing body dissatisfaction. Why are puberty blockers continually held to inappropriate standards? [Answer, this is intentional, if they are held to appropriate evidence standards they easily pass]

WHOSE VOICE MATTERS? Part d of the conclusions (again, should be obvious) is notable. “there is no evidence that PB should always be used before starting GAHT”. If the review actually centred trans individuals’ healthcare autonomy, it should be obvious that puberty blockers as monotherapy should not be forced onto all trans youth. This is yet another indication that the review is taking an approach to healthcare as though healthcare service users don’t matter. Where is the centring of patient autonomy and decision making? This problem is inherent in healthcare services that try to ‘treat’ the condition of gender dysphoria (centring the view of a clinician on what is the most effective treatment) as opposed to healthcare services providing healthcare to trans communities (centring the views of what trans individuals want/need to access). Of course trans youth who want to access HRT should not be forced onto blocker monotherapy – this conclusion needs to be framed as a conclusion in favour of patient autonomy, not in terms of the evidence base.

WHAT ARE THE HARMS? For a treatment that is strongly desired by trans communities, strongly endorsed as beneficial by trans communities, strongly supported by clinicians who want to deliver that care, any evidence review needs to consider what would be the evidence base for prohibiting it. Especially for a minoritised community facing calls to outrule all healthcare, there is surely a duty on healthcare reviews to establish a bar of necessary harm in order to outrule such care. Here there is no strong evidence of harm from this care. Yet this conclusion – what is the clear (high quality) evidence of harm? There is none, yet this does not make a bullet point. The bias is clear – trans healthcare needs to be continually defended – and those opposed to it do not even need to produce evidence of harm. This mismatch in evidence thresholds is core to all recent anti-trans reviews such as the cass review. Evidence is support of care is never good enough. Concerns about hypothetical harm is taken extremely seriously, no matter how flimsy or non-existent the evidence of harm is.

On page 36 a section of ‘the commission also heard’ a list of important pieces of evidence that are all really meaningful, all of which should guide the review towards individualised trans healthcare.

The Panel heard in consultation:

· from individuals with lived experience and their families, experiences of distress at the prospect, and experience, of developing secondary sex characteristics through natal puberty; · from clinicians and individuals with lived experience, that PB give ‘thinking time’ to young people to explore their gender identity and for their family and clinicians to consider persistence, insistence and consistency and decide whether GAHT is right for them without developing potentially distressing secondary sex characteristics through natal puberty; · from clinicians and individuals with lived experience, that the timing of PB is critical in that they prevent or halt development of secondary sex characteristics but have minimal utility for adolescents presenting to a service at a later developmental stage; · that long waitlists can prevent young people from accessing a PB prescription before their puberty progresses beyond the developmental stage where PB may assist; · that use of PB during early puberty before progression to GAHT results in better passing in the future which is psychologically relieving to young people at the time and in the future, lowers risk of future stigma and discrimination surrounding being identified as transgender and decreases the need for future surgeries such as top and voice surgeries; · from some clinicians, individuals with lived experience and families, that PB prescriptions have assisted school attendance and engagement and psychosocial functioning and experiences of PB assisting with health issues, including suicidality and eating disorders relating to an attempt to prevent pubertal development; · from some clinicians, individuals with lived experience and families, experiences of young people at times feeling socially isolated on PB as they are not progressing through puberty at the same time as their peers and some experiences of psychosocial developmental delays; and · from clinicians, awareness that PB should not be prescribed on a long term basis and that there is a point where the young person must either begin GAHT or cease medication.

The above, combined with no evidence of significant harm, would be highly convincing in favour of any area of healthcare not informed by prejudice.

On this page, in a footnote, the authors also note the way that the Utah Review considered this evidence base:

“The Utah Review concluded at page 90-91 that, “the consensus of the evidence supports that the treatments are effective in terms of mental health, psychosocial outcomes, and the induction of body changes consistent with the affirmed gender in paediatric gender dysphoria patients. The evidence also supports that the treatments are safe in terms of changes to bone density, cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic changes and cancer. … it is our expert opinion that policies to prevent access to and use of GAHT for treatment of gender dysphoria in paediatric patients cannot be justified based on the quantity or quality of medical science findings or concerns about potential regret in the future, and that high-quality guidelines are available to guide qualified providers in treating paediatric patients who meet diagnostic criteria”.

The Vine Review should have been more transparent in answering the real question it was tasked with: “Is there medical evidence to justify the denial of this area of healthcare”. The Utah review was honest about having this as its key task, and answered it clearly “it is our expert opinion that policies to prevent access to and use of GAHT for treatment of gender dysphoria in paediatric patients cannot be justified based on the quantity or quality of medical science findings”.

Service user involvement

On p.39 the vine review notes an important criticism of current literature: “no studies reported patient or stakeholder involvement in design or conduct which highlights a critical gap in the relevance and applicability of the evidence”. It is erm interesting, that they disregarded qualitative literature here, a place where patient voice can be found. It is also clear that the Vine review has not considered the incompatibility of trying to centre patient priorities, and achieving an evidence base that will satisfy critic. The two are highly incompatible, and this needs to be recognised. Critics will continually ask for more assessment, more domains of measurement, longer term follow up, and a focus on the treatment of a psychiatric diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Service users will demand rights respecting healthcare that is not subject to excessive and harmful assessment, the right not to ensure life time study, and the need to centre the outcomes that matter to trans young people, not impacts on a deeply dated and flawed diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

Effectiveness of the treatment

Associated with the Vine Review is a literature review from Joanna Briggs Institute at the University of Adelaide (JBI). The conclusion of this literature review as stated on p.39 of the Vine Review is “that no generally positive benefit-risk assessment of PB for the treatment of gender dysphoria of young people can be made on the evidence”.

Their core basis for this statement is “although the evidence for short term benefit in psychosocial areas may be trending towards positive. Evidence for cognitive, bone, fertility, and long term physical health outcomes remains inconclusive or inconsistent, with limited data to assess risks or sustained effects.”

The very next section goes on to say “Effectiveness in suppressing puberty 121. PB are the most effective treatment for suppression of puberty, with no other agents having been shown to be efficacious in this setting”.

The evidence review is always rigged to show ‘no evidence of impact’ whilst also showing ‘PBs are very effective at suppressing puberty’. If patient autonomy was respected, the fact a particular individual ‘wants to avoid incongruous puberty’ would be centred as the treatment goal, and there would be no question of the ‘effectiveness’ of puberty blockers. It is only because we are in this quagmire of determining ‘effectiveness in treating gender dysphoria’ that we are forever being asked for evidence of effectiveness, for a treatment that is very clearly and uncontrovertibly effective at its key purpose (preventing an unwanted puberty).

Again, no consideration of harms of denying care

I am so tired of this type of evidence review. They state (p,41) that “on psychosocial outcomes indicated improvements in depressive symptoms, anxiety, suicidality and quality of life”. They caution that “certainty and causality are low due to the methodological limitations of the research”. Why would you ban a treatment, with no evidence of harm, with this type of indicated benefits, simply due to “methodological limitations of the research”. It is bad faith all the way down.

The answer to this is not to improve the methodological quality of the evidence base, it is to rigorously recognise and challenge the forces that are using questions of methodological quality to try and cancel a treatment that they are ideologically opposed to. Those raising concerns need to be told to come back with rigorous evidence of harm or to go away. I am so tired.

Another double standard

Another double standard appears on p.45. When assessing the benefits of PB, evidence of the positive impact on mental health when combined with HRT is apparently not eligible for consideration when evaluating puberty blockers. But, when considering the risks of puberty blockers for fertility, the assumed addition of HRT is included in the evaluation of risks.

Value of autonomy

Page 45 includes important input from those with lived experience on “the value of autonomy in a decision of whether to accept risks of a course of treatment based on the relative importance of the possible risks, benefits and unknowns to them”. This important conclusion is not emphasised in Vine review reflections.

Even those adults whose cared more about fertility as they got older, said that they would not retrospectively change their decision to pursue affirmative medical care “due to the beneficial outcomes they experienced”.

There are some parts of this report that are well written, have good content, particularly the ‘in consultation’ boxes. It feels different to the Cass Review, that was rotten throughout. It smells like a report that started out good, drew upon solid work by more junior folks, and was tweaked and made worse at a top level for political fit (purely my speculation). In the Cass Review it seemed as though every section was authored by those ideologically against trans healthcare. Here the picture is much more mixed.

Failing to centre individualised rationales for healthcare.

P.46 “A rationale for PB use is to improve longer term societal acceptance in the individual’s gender identity”. The reasons for using puberty blockers are presented as though trans youth are a uniform group. There is not enough recognition that every individual is different, may have different priorities, and may want to make a risk benefit analysis of their options differently, shaped by their different priorities and concerns. The need to make an all encompassing ‘rationale’ for puberty blockers stems from the assumption that this is a ‘treatment’ of a ‘condition’, rather than a part of bodily autonomy for a marginalised group. Once you centre bodily autonomy, it is obvious that individuals will have different priorities and different ways of viewing the purpose of puberty blockers or HRT. If you centre individualised healthcare decision making, evidence also moves from a binary is there good enough evidence to allow this or should be ban it (the territory of the Vine Review), to asking what evidence do trans young people need to make individualised informed decisions, and how can we better support informed decision making.

Evidence double standards again

P.47 In one section there is a claim of insufficient evidence of reversibility when PB are stopped without HRT. This is clearly nonsense squared. They don’t even put this into scientific terms. What are they saying is not reversible? Are they saying hormone levels of endogenous hormones don’t increase? Are they saying something else? It is all very vague and unscientific here. If there is a specific concern about some irreversible impact, they need to evidence it – this type of completely unevidenced speculation, that happens to align with anti-trans scaremongering, shouldn’t appear in a report that claims to hold itself to high quality evidence. Another double standard in the very high quality evidence needed to support care, and the flimsy or non-existent evidence that is counted when undermining it.

Burden of proof

In the next box they state “opposing interpretations of whether PB are reversible when used for paediatric gender dysphoria”. But is there any evidence of it not being reversible? What specific areas of non-reversibility have been proved (even anecdotally). Why is there absolutely no minimum standard of evidence for which to critique this healthcare? When making a specific claim (it is not reversible), for a healthcare that has been used for decades, the burden of proof should be on those who are raising this concern to demonstrate that it is not reversible. The burden of proof shouldn’t always be supporters of affirmative healthcare, to prove that a totally unsubstantiated ‘concern’ is not true.

If we allow any unsubstantiated concern to be taken seriously (again, in healthcare used for decades, where that concern is not considered important in cis people), and if we require the affirmative side to produce high quality evidence that this made-up concern is NOT true, then we set ourselves up for continual failure. Trans healthcare can continually be kept under accusation of ‘not proven’, because the goal posts can continually be shifted to new domains of made-up concern. We have already seen this happen over the past decade.

In medicine perhaps there is a tendency to see ‘no smoke without fire’. To investigate rigorously whenever people raise concerns about unintended impacts. But we need to recognise the world we live in – a world shaped by transphobic prejudice. Anti-trans actors will always raise concerns about impacts. There needs to be a burden of proof on those raising concerns to specify and justify their concerns. In trans healthcare, nevermind justify and evidence, they often don’t even specify their concerns. We have concerns over ‘impact on psycho-sexual development’ without even stating what those concern actually are. Here we have concerns over reversibility, without even specifying what irreversible impact they are claiming may occur.

P, 47 has a pretty clear and strong conclusion: “In summary, it appears from the available research that the effects of PB are reversible. They are best started early in puberty and for a limited time. Unwanted side effects are rare, provided there is regular monitoring of relevant hormone levels. If used later in puberty, there may be more side effects, and it may be more appropriate to consider other treatments to address the symptoms or issues which are causing concern, such as menstruation… Having considered the JBI literature review, previous reviews and studies and available guidelines, we have concluded that, with proper oversight and appropriate reporting, there can be benefit for a young person in being able to access PB.”.

It then moves into the unevidenced:

“We support treatment only being considered after assessment by a MDT with experience and expertise in this area and only after any other causes or contributors to the young person’s distress have been considered and resolved to the extent possible”. This latter part is entirely unsubstantiated by the preceding evidence review. Apparently evidence must be rigorous when considering a treatment, but strong requirement can be added with zero evidence when this infringes on trans youth healthcare rights.

Why does this very clear statement on the overall support for puberty blockers not make it into the Vine Report Summary of Recommendations or executive summary? Earlier sections of the report focuses only on the limitations of the evidence, not on this recommendation in support of the care.

Here I’ll stop this part of my reading of Vine, having got to p.48.

On HRT

On HRT it notes (p.50) “Overall, the evidence suggests that the treatments induce the desired physical changes and that there is increasing evidence suggesting positive psychosocial outcomes. The evidence also suggests that, in healthy people, apart from the impact on fertility, the risks to bone health and of cancer and cardiovascular events are low and comparable to those in cisgender counterparts.”

Again, did I miss where that is stated so clearly in the exec summary and recommendations? Those bits very much focused on risk, what is unknown.

On HRT effectiveness

The Utah review is quoted in HRT being “effective in terms of the induction of body changes consistent with the affirmed gender in paediatric gender dysphoria patients”.

Why does HRT here get to be evaluated in the terms in which it is used by trans people (to induce affirmative bodily changes) yet puberty blockers aren’t evaluated in the terms by which they are used by trans people (preventing unwanted pubertal changes). Evaluating effectiveness is far more reliable when they are assessed to the purpose that makes sense for healthcare users (preventing non-affirmative or enabling affirmative bodily changes) than in treating an ill-suited diagnosis (gender dysphoria).

Surely this could be considered a basic requirement for evaluation of medical care – evaluate according to the purpose/desired impact of that medical intervention as defined by those taking it.

Trans healthcare goes astray because there is too often no correspondence between the reasons why trans people seek trans healthcare and the ‘treatment goal’ defined by cis clinicians.

False middle-ground

I really disliked the part on page 57 where the Vine review notices polarisation and tries for a middle path “adopting a practical lens that does not engage with these extremes”. There is no recognition that one of the extremes, those fundamentally opposed to trans existence, needs to be isolated and ignored. And that there is no such group at the other extreme – indeed, the suggestion that those fighting for rights-centred healthcare should not be positioned as an extreme group at all. Positioning yourself halfway between the policy of a hate group and a rights-centred group is not an acceptable position.

The Queensland service.

Some description of the Queensland service is provided.

It is described as an affirmative service, “which considers no gender identity outcome: transgender; cisgender or otherwise to be preferable”. The Vine review includes criticism of this approach, without recognising that the alternative to an affirmative service is a conversive approach, and without recognising that trans young people have a right to an affirmative service as a basic component of healthcare dignity and equality.

It makes space for the argument that “the initial assumption of gender affirmation may not be appropriate in the developmental context of children with differing presenting histories, where there may be uncertainty on the part of one or both parents or a lack of clarity regarding diagnoses”. These arguments are presented as acceptable reasons for wanting a non-affirmative service, without considering the significant harms that would result.

The level of assessment required is a potential concern (for me, not for the Vine Review, the Vine review wants more of this) (90 min intake assessment, to be followed by a bio-psycho-assessment (of unstated length) before being taken to MDT panel for decision making.

The description of the MDT panel is a potential concern (for me, not for the Vine Review, the Vine Review wants more of this). It notes that all staff in the service are part of the MDT panel and “”medical treatment will be offered where all members of the multi-disciplinary team agree that treatment is in the adolescent’s best interests as confirmed at a multi-disciplinary case review”.

This emphasis on requiring unanimity is a concern, especially noting the significant risk that this places on a service. Even just one gender critical clinician could prevent all gender affirmative care in this model. I’ve seen this happen in several locations.

And beyond this specific risk, why are large teams of clinicians by default required to take joint decisions on access to a simple form of healthcare. It seems like a defensive practice model of shared responsibility, rather than centring what is best for an individual service user. It also reinforces complexity and the need for not just one clinical judgement, but many clinical judgements, taking us further away from the idea of informed consent and decision-making removed from clinician gatekeeping and control. Why would multiple professionals, some who have never met the adolescent, be required, by default, to hold power over their access to healthcare [Note, this is not an argument for them to all meet and question the adolescent, this is the UK model and is even worse].

The average waiting time in 2024 was 505 days.

The model of care in Queensland is described thus:

The draft model of care describes QCGS assessment as including: (a) mental health risk assessment in the SSFT session, initial MDT care review and as required; (b) gender assessment after SSFT; (c) physical health screening if PB or GAHT is being explored; and (d) neurodevelopmental/cognitive assessment if diagnostic clarification of neurodevelopmental disorders serves a functional purpose for QCGS assessment.

Interventions focus on: (a) single-session and brief interventions; (b) risk assessment and crisis interventions; (c) pharmacotherapy; 191 QCGS Service Evaluation, pages 50 – 52. 192 Work Instruction as effective 5 February 2025 page 4. Work Instruction as effective 21 February 2024 page 3. Independent Review Advice Report 63 (d) interventions that promote parental/system capacity to coordinate care quickly; (e) education on gender diversity; (f) advocacy; (g) support with social transition; (h) chest binding; and (i) care coordination

Data on service numbers are on page 63.

Dealing with cisnormative parents

A review of this nature seems entirely ill-equipped to deal with input from transphobic, cisnormative or uninformed parents, even though this input is entirely to be expected.

Quotes like this are provided:

“some parents, described feelings of grief or loss when their child persisted in their TGD identity, and that those parents did not feel their experience was recognised”.

“some families, described feelings of concern that affirmation was seen as the inevitable and desired outcome, and that there was insufficient consideration of alternatives to PB and/or GAHT”

One role for services such as this is to educate and inform parents, whilst centring the need and rights of the child/adolescent. The Vine Review and similar reviews needs to centre the healthcare rights of children through this process. It should have expected some amount of feedback from parents who would rather their child had conversion therapy, and this feedback needs to be noted, but not be accepted as meaningful criticism of the current service model.

In a world where parents are at different levels of knowledge, holding different levels of prejudice, it is never possible for a service to meet the expectations of all parents. Critique needs to be reviewed through a lens of a commitment to depathologisation and trans and child rights.

“from some service users, that the typically slow assessment process was an endorsement that the assessment of the young person and their family was thorough, though others considered it overly cautious”. Again, the Vine Review is taking this as differences of opinion, whilst not recognising that some parents want their child to be grilled and challenged on their trans identity, while other parents want do not want their child to be put through unnecessary grilling.

I don’t like the way that the Vine Review groups parent and child together as ‘service users’, without clearly distinguishing when an opinion is from a child vs from a parent. Were the children actually saying that they were pleased with the thorough assessments?

On Data

“from some individuals, requests for long term follow up data collection to be made mandatory, and others concerns about privacy and opposition to being forced to participate in research or a trial”. Again, the Vine Review is hearing from different groups here. Trans young people have a right to data privacy and should not be forced into long-term research. Healthcare services need to uphold patient rights.

Two other important points noted in ‘panel heard in consultation’ boxes:

“concerns that a sole focus on gathering data to increase the evidence base may be at the expense of people that currently need treatment”

“that decreasing access to the treatments would result in large scale data being difficult or impossible to access or obtain”.

Reasons to not diagnose as per the Queensland service spec

(a) the young person not being TGD; (b) the young person having no dysphoria in relation to their body (no diagnosis of gender dysphoria); (c) the young person being ambivalent about starting hormone treatment; (d) parental disagreement; (e) the person being too young (pre-pubertal); (f) the person being unable to consent (for example, due to the impact of mental illness such as psychosis or if the young person is assessed to not have capacity); (g) the treatment being not safe socially due to factors such as unstable accommodation or out of home care; or (h) other medical risk.

Private providers

There is reference to private providers (P,68-69). Does seem to potentially be setting sights on restrictions there…

UK and Finland

The Vine Review panel looked to UK and Finland, two of the worst locations in the whole world, for input on alternative models. What a surprise that they stumbled upon that combination. Noone would assume UK + Finland is the ideal comparator for Australia – this is clear an indication of anti-trans influence.

On p,70 the JBI literature review describes “several European jurisdictions have moved toward more precautionary, research-based approaches”. This is false. The shift in places like the UK has nothing to do with caution or the wellbeing of young people, nothing to do with research-based approaches (the new approach has no research to back it). Their shift is everything to do with ideological and prejudice impacting on healthcare. The JBI summary is inaccurate.

Prejudice

Again, there is no recognition of the role of prejudice in this description “reports from the USA (DHHS Review and Utah Review) reaching different conclusions” (p.70). The DHHS Review did not just happen to come to different conclusions. It was ideologically established in order to remove access to trans healthcare. The Vine Review is trying to avoid any recognition of the role of prejudice in this field.

Expert opinion

It is really interesting that the JBI report takes expert opinion as sufficient to underpin guidance that raises barriers to care (on the need for comprehensive assessment and an MDT) but insufficient when it comes to access to care (on the importance of blockers or HRT).

Some of the sections quoted from JBI report 2 (that I haven’t read yet) are really problematic (p.70-71).

Professional liability

p. 76 has an interesting section on liability, that defines care as meeting acceptable standards where it “was widely accepted by peer professional opinion by a significant number of respected practitioners in the field as competent professional practice”. Professionals seem to be being pushed into ever more comprehensive (and abusive) assessment in a shift to defensive practice – professionals at Auspath were discussing documenting assessments in ever greater detail in case of legal cases where they needed to prove that they had indeed assessed everything. From the content in this section it does seem that another option would be possible – for Australian professionals (in significant numbers) to instead commit to rights-based practice, removing the need for this defensive practice emphasis on defending the comprehensiveness of an assessment and diagnosis.

This section doesn’t even consider the ethical dimensions of denying access to necessary healthcare.

Conversion therapy

There is a section on conversion therapy that entirely fails to consider when psychological therapy would cross into the territory of conversion therapy. It is quite bizarre how this isn’t even dealt with. Apparently, the legislation “does not prohibit any practice that is based on reasonable clinical decisions about how to provide safe and effective care”. A lot, it seems, hangs on the world ‘reasonable’.

It states “The Panel concludes that clinically appropriate full assessment of a person’s gender identity and any dysphoria related to that identity with no preferred identity in mind that aims to facilitate care and/or to support a person in managing the psychological impacts of their gender dysphoria/incongruence, should not fall within the definition of ‘conversion therapy’ above.”

Again, ‘clinically appropriate’ is something that needs to be understandable to make this legislation any form of actual protection for trans kids. I wonder if AUSPATH will write something on what is not clinically appropriate in terms of talk therapy or assessment for trans kids. This is even more important in services that are unable to offer any support for medical pathways, because those services will need to fill their time doing something.

Human rights

p.83 has a section on the human rights legislation impacting on healthcare. I will mention here my recent article with Ruth Pearce on trans childrens’ rights.

The right of trans children to access trans healthcare is waved away through reference to the lack of consensus and the lack of rigorous enough evidence that trans healthcare is an effective ‘treatment’ for the mental health disorder of gender dysphoria. The Vine Review did not start with anything like enough understanding of the historical and clinical pathologisation and psychiatric control of trans communities, and this can be seen in this section.

Privacy

The section on privacy comes from the perspective that it is a shame that trans kids have privacy rights. It seems to suggest that privacy and health data rights could be overcome if only PB and HRT were defined as ‘monitored medicines’ – medicines that are considered as potentially presenting a high risk of harm to patients…

Woe for criticised professionals

Here (p,89), as we saw in Cass, one section focuses on how hard it is for professionals if they get criticised or investigated for not being affirmative. There is no recognition of the harms of non-affirmative practice, the huge power imbalance between child and clinician and the lack of accountability mechanisms. This section also did not talk about the protection for clinicians who are attacked (often backed by Right wing funding) for being affirmative.

Risk of not

p.90 “The risks and benefits of not intervening must also be carefully weighed, including the ongoing impact that some participants described of developing irreversible and unwanted secondary sex characteristics which contribute to enduring distress into adulthood”

But that sensible statement is followed by this one:

“medicating otherwise physiologically healthy children and adolescents to help in managing their internal distress in the face of wider societal misunderstandings of gender diversity may create a disproportionate and indefensible burden on them”.

Ew Vine Review

Diagnosis

p.90 deals with diagnosis very poorly. It contrasts patient autonomy with ‘diagnostic certainty’. But at no point does it deal with the fact that ‘need for puberty blockers’ or ‘need for HRT’ really can’t be diagnosed. The diagnosis of gender dysphoria is a very vague diagnosis anyway, and those hiding behind ‘diagnostic certainty’ are lying to themselves or others. Need for trans healthcare comes from listening to the individual patient and helping them take informed decisions – it is not a medical condition to be diagnosed with certainty.

Stigma

p.91 has a whole section on stigmatisation, marginalisation and discrimination, without once mentioning pathologisation, psychiatric control, or healthcare violence towards trans people.

Funding

“Allocation of funding is premised on a condition that interventions are effective”. “Services must demonstrate efficacy to justify continued funding” Here the terms are set up for defunding healthcare that is not deemed effective. Trans healthcare is one of the most effective and cost-effective areas of healthcare, with very high patient satisfaction. But here a lack of high quality evidence can potentially be utilised to defund such care.

P, 92 “Analysis, review and reflection on outcomes is therefore critical to justify ongoing funding which is appropriately targeted to achieve the best short and long term health outcomes for the diverse group of young people increasingly presenting to Queensland HHSs with gender-related distress.”

No centring of trans children and trans adolescents. Here we have young people with ‘gender related distress”. And who knows what ‘treatment’ best resolves ‘gender related distress’. Maybe denial of trans healthcare…. Maybe talk therapy… Maybe shaming kids back into the closet.

Diagnosis

Again (p,92), some of the boxes in this report are actually good.

“views that a diagnosis is pathologising and a source of oppression, and that medicalisation of TGD identities is unnecessary and stigmatising”

“that diagnosis is a barrier to access to treatment and should not be required to access GAHT treatments – some individuals reported that a desire for treatments of a child with agency is sufficient justification”

“that adolescents can experience less dysphoria than required by the diagnostic criteria but still want and may benefit from PB and/or GAHT, and may be unfairly excluded from treatment in the public system if diagnosis is used as an essential criterion”

Though some junk in there too..

Some of these boxes don’t seem to influence the core report conclusions at all. It is interesting which evidence and input shapes the report conclusions and which is noted and then side-stepped

Trans broken arm

The report acknowledges trans broken arm syndrome (p. 94) but then immediately talks about the opposite, diagnostic overshadowing.

P,95 has this absolute bullshit “Our view is that a person/child centred approach warrants the full assessment and early management of any co-occurring conditions before initiation of PB or GAHT.” This is not justified at all. There is no gold standard evidence of this requirement, that is pulled from the sky.

Noticeably this appears in a section referencing neurodiversity.

Coercion

I actually laughed out loud at this one. There is exactly one use of the word ‘coercion’ in this report. In a report on trans healthcare, an area of medicine that has historically been exceptionally coercive to young people.

This is the one acknowledgement of coercion (p,96): “The Panel also heard perceptions that a coercive environment is created when unquestioning gender affirmation, with or without access to PB or GAHT, was expressly linked to reduced suicidality for young people experiencing gender-related distress”.

Recognising the very real risk of hopelessness and suicidal ideation/attempt in young people denied essential healthcare, is the one place where the Vine Review talks about coercion.

Wow.

It then moves to look at Finland as a model. A place where the reports of healthcare violence and coercion from young people are off the charts.

Why do you think the Vine Review finds Finland the go-to model of healthcare for Australia? Is this common in other areas of Australian healthcare? Or is this a bit of an unusual reference point. The Finland state system is one of the last places I would look for advice on good healthcare for trans children.

Diagnosis

p.96 we are back to diagnosis.

Here more of the reasons to not want a diagnosis of gender dysphoria are covered.

The reason for wanting access to trans healthcare based on ‘felt need’ are mentioned. These are dismissed on practical grounds of needing to rationalise health expenditure (an argument entirely different to the argument around accurate diagnosis above). This statement is made “The practical necessity of the diagnosis of gender dysphoria as a pathway to treatment is acknowledged by some critics of the use of diagnosis.” One citation is provided. If you read that citation, it explicitly argues against gender dysphoria as a diagnosis, considering it outdated and pathologising. It suggests that the principle reason for utilising the more acceptable gender incongruence diagnosis is because a ‘term’ is needed for reimbursement purposes in diagnosis-oriented health insurance systems. This article does not upholding the need for a psychiatric diagnosis of which people suffer acute enough gender distress to access trans healthcare and it is misrepresentation to present it as evidence of ‘the necessity of a diagnosis of gender dysphoria.

This section would do well to consider parallels with other areas of health based on bodily autonomy, including abortion care, pregnancy care and reproductive healthcare. There is a reason why the revised ICD diagnosis has moved to reproductive health rather than psychiatry.

Social transition

“For some young people, social transition is an active step in managing gender dysphoria”.

This is so messed up. This is what happens when trans existence is framed through the lens of psychiatric treatment. Trans people aren’t socially transitioning to “manage gender dysphoria”. They are socially transitioned to stop hiding who we are and to embrace life authentically and with gender euphoria. Putting a psychiatric treatment lens on social transition is bad form Vine Review.

(this also opens the door to defining it as a medical intervention, needing clinical permission, as we are seeing in the UK)

“While social transition is physically reversible, the ongoing psychological benefits or harms are not yet fully understood”

No Vine Review, you don’t get to have opinions on the psychological benefits of using a new pronoun. Get in your lane.

P,98 Social media

This section is problematic. The word grooming is used to reference affirming communities on Reddit. It is unclear if they are referencing risk of actual grooming, using this term to talk about affirmation. Instead of centring the actual risks trans young people can face with social media, alongside the sizeable benefits, the focus is on parental experiences of being called transphobic for wanting to question or challenge a young person’s identity.

Affirmation

P,99 has a whole section on how affirmation shouldn’t entail using a young person’s pronoun or “an immediate acceptance of the gender the young person reported”. Gross. The Vine review here moves into wanting non-affirmative practice dressed up in the language of affirmation.

If you accept “consider no gender identity outcome to be preferable”, then of course you will accept and not problematise the gender that a young person describes themselves as.

If you problematise and do not accept the self-description of a young person, but only when they are trans (assuming you don’t do this in clinical practice with cis kids), then you are clearly suggesting there is a problem with a trans identity.

Why is the Vine Review trying to change the accepted meaning of affirmative care, and trying to push for non-affirmative approaches through the back door?

“outward facing symbols may lead to premature foreclosure or ‘settling’, potentially limiting ongoing genuine exploration in the child’s best interests”. Love it when the psychobabble comes in. Premature foreclosure indeed. Genuine exploration in the child’s best interest. Hmm.

P.100 I’m going to stop here, cos this is already ridiculously long.

Why are all these healthcare reviews both a) so long and b) so bad that it takes pages of notes to even scratch the surface with what’s wrong with them. One final point

Systematic Reviews and Qualitative Literature

I looked briefly at the JBI literature review that underpins the Vine Review. It is yet another Review of Evidence that claims to be comprehensive, that claims to include qualitative literature, that yet again is absolutely terrible at it, excluding nearly all the qualitative literature. It is really not good enough to claim to cover qual literature, and to conclude that there is only one (not peer reviewed) qualitative study on puberty blockers. The fault here comes down to a lazy search strategy.

Here they search three databases, all focused on psychological or bio-medical literature. The first two databases exclude the majority of qualitative literature. PubMed only include literature funded by major funders, which is likely to include the bulk of expensive clinical studies, but largely excludes inclusion of qualitative literature which is less likely to receive big institutional funding. Embase focuses on biomedical journals, and does not include the many qualitative healthcare experience articles that are usually published outside of biomedical journals. The third database, Psych info, focuses on psychology and social sciences. It does appear to include a greater range of qual relevant journals. It is strange that the authors of the JBI literature review claim to have done a comprehensive search of Psych info, and yet to have found zero peer reviewed qualitative articles on the topic of puberty blockers. Is this a problem with the database Psych info, or did the authors fail to do a proper search for qualitative literature? I cannot access the Psych info database search, so I can’t test whether more of the qualitative literature, including my own work, appears in there.

It is a recurring pattern in trans healthcare that literature reviews that claim to be comprehensive, that claim to include qualitative literature, fail to find that literature, often finding one or two articles at most, when there is a huge body of qualitative literature on trans health.